Methodology for Legal Analysis

Legal analysis in the broad sense refers to a statement by a court, judicial officer, or legal expert as to the legality or illegality of an action, condition, or intent. It can be a written document in which an attorney provides his or her understanding of the law as applied to assumed facts. The attorney may be a private attorney or attorney representing the state or other governmental entity. Private attorneys frequently render legal opinions on the ownership of real estate or minerals, insurance coverage, and corporate transactions.

Legal Analysts are legal specialists who support and aid individual lawyers or legal teams. They conduct legal research, assemble legal documents and evidence, maintain databases and tracking systems, and track, organize, assess and file documents

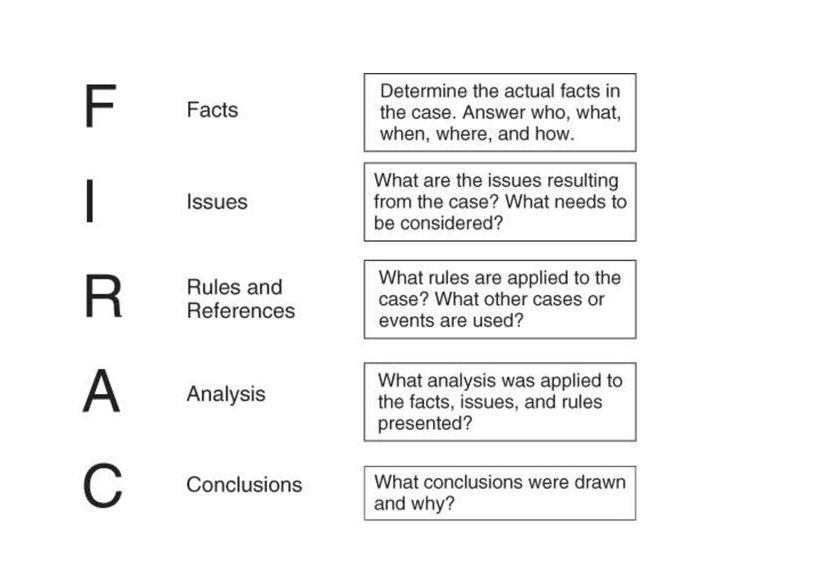

FIRAC (an acronym for a five-step analytical process)

F – Fact I – Issue R – Rule A – Analysing C – Conclusion

F – State the Facts of the case

Case refers to an actual, potential, or hypothetical dispute which raises a question of whether one or more laws were violated. A lawsuit is an example of a case.

The beginnings of material or key facts may be unearthed by the question – “what extra facts might be relevant to the final outcome of this problem/dispute”? The sources of key facts could be events, dates, people, documents and statutes. It may be based on the queries – WH5 – What? When? Where? Why? Who? How?

The “facts” of the case describe what happened to cause the dispute. The facts may describe behavior, who or what engaged in that behavior, the reasons for the behavior, when and where the behavior occurred, why or the circumstances at the time the behavior occurred, who or what was affected, how they were affected, and so on.

Some facts are more important than others, and the most important facts are the key facts—those facts upon which the outcome of the case depends. Key facts are those facts necessary to prove or disprove a claim. A key fact is so essential that if it were changed, the outcome of the case would be different – key facts are an element of a legal issue.

A material or key fact may be described as a fact which is of vital importance to a line of deductive reasoning in order to solve a problem or to give helpful advice on a range of options in response to a particular issue or social problem. Pinpoint the determinative facts of the case, i.e. those that make a difference in the outcome. Your goal here is to be able to tell the story of the case without missing

I – State the Issue

Lawsuits are brought because one person believes another has violated some law. Thus, the primary “issues” a court has to answer is whether a named defendant is guilty of or liable for violating a specific law.

The issue sets up the problem. What happens in the remaining steps depends upon the law issue identified in this step. Change the issue and everything that follows also changes. Among other things, this means that when the facts give rise to multiple law issues it is necessary to do a separate FIRAC analysis for each issue.

“Issue spotting” may seem easy but don’t be misled. There are so many variables at work that a law issue may remain hidden in plain sight. The facts may be screaming that a law has been violated but you will be oblivious to the outcry if you are ignorant of the law. You may know everything about a law except for the key piece of information needed to make the connection in that particular fact situation before you. You may misread the facts or fail to pick up on a nuance. Time pressure may cause you to overlook something that would have been apparent if you had not been in a rush. A haphazard approach may miss things that a systematic approach would find.

Not noticing a law issue, for whatever reason, have consequences. To not ask a question is to forfeit the answer and all the associated benefits. Overlooking a law issue in a real case can mean a damage award that might have been, a defense that never was, or an upset client.

The “I” step is only about recognizing the question. Figuring out the answer is the purpose of the remaining steps. Even if you are absolutely, positively certain you know what the answer is, restrain the urge to jump to the “C” step. Your initial reaction could be wrong. You may have overlooked a critical fact. Your understanding of the law may be incorrect. Bias or emotion may have influenced your perception. Doing a complete FIRAC analysis is the only way to catch such errors.

An issue is a single, certain and material point arising out of the allegations and contentions of the parties; it is matter affirmed on one side, and denied on the other, and when a fact is alleged in the complaint and denied in the answer, the matter is then put in issue between the parties. In the issue section of an FIRAC it is important to state exactly what the question of law is. It is a statement of the general legal question answered by or illustrated in the case. To find the issue, ask who wants what 4 and then ask why did that party succeed or fail in getting it. Once this done, the “why” should be turned into a question?

R – State the Rule of law that applies

The “rule” is the text of the law that was identified in “I” step or the legal principle. What is needed is a quotation of the rule, preferably from a primary source or the restatement of the legal principle. The name of the rule is not sufficient. Neither is a paraphrased statement. In the application step, words of the rule will be compared to the facts. The words of the rule also provide information needed for the conclusion step. If the rule is not expressed accurately here, the rest of the analysis will be flawed.

The rule section of an FIRAC is the statement of rules/legal principles/precedence pertinent in deciding the issue stated. It is a legal summary of all the rules used in the analysis.

A – State the application – analyze the situation by applying the rule to the Facts

The application section of an FIRAC applies the rules developed in the rule section to the specific facts of the issue at hand. It is important in this section to apply the rules to the facts of the case and explain or argue why a particular rule applies or does not apply in the case presented (develop arguments on both sides of the issue being dealt with). The application section is the most important section of an FIRAC because it develops the answer to the issue at hand.

An “application” is, in essence, a comparison of two sets of words: the words of the rule that describe the conduct it prohibits/requires/permits and the words (facts) that describe the conduct that occurred. The task is to ascertain whether two sets of words describe the same conduct. The words of a rule describe certain conduct. Those words have been chosen with care to create a precise and unique description of that conduct and to distinguish it from conduct not covered by the rule. The result is a list of separate and identifiable things which have been combined together in sentence form. One word or phrase of the rule may describe a specific behavior. A different word or phrase may describe who must have engaged in that behavior; or a state of mind that must have been present while engaging in the behavior; or circumstances that must have been present when the behavior occurred; or who or what must have been affected by the behavior. Other words may describe other things. Each of these things is one element of the rule.

The best way to do an application is to compare each element, one at a time, to the facts. Each element describes one part of the conduct covered by the rule. By proceeding methodically through all the elements, each and every part of the conduct is compared to the facts. Nothing essential is overlooked and nothing extraneous is considered.

Begin by converting each element into an element issue. An element issue is a question that asks whether an element is satisfied. It may be stated in general terms, 5 such as “was there smuggling”? It is preferable, however, to phrase an element issue as a question that states the relevant facts and asks whether they come within the meaning of the element. “Was the act of being caught at a fixed checkpoint with tobacco product without paying tax amount to smuggling”? Is a better statement of an element issue than “was there smuggling”?

An element is “satisfied” or “met” if the thing described by the element (who, what, circumstance, etc.) is also described by the facts. If all the elements are satisfied, the rule and the facts describe the same conduct. But it’s all or nothing. Close doesn’t count. There must be a perfect match. If one or more of the elements are not satisfied, the rule and the facts describe different conduct. There may be some other rule that encompasses the conduct – but not the one you are analyzing.

Just like a matching game can be tricky, so can an application. Grammar and punctuation can affect how a word or phrase should be interpreted. A word may have multiple meanings. If you think an element means one thing but the legal definition is different, you will be searching the facts for the wrong thing. It is all too easy to misread, overlook, or ignore relevant facts, consider irrelevant ones, or assume the existence of facts that are not stated.

C – Reach a Conclusion

Every rule, in addition to describing certain conduct, also states a conclusion to be reached when that conduct occurs. It may help to think of the rule as an “if-then” statement: if the conduct described by the rule occurred, then the conclusion stated in the rule should be reached. The comparison conducted in the application step provides the information needed to determine whether the “if” condition has been met. If all the elements were satisfied, the conduct occurred. If one or more of the elements were not satisfied, the conduct did not occur.

The conclusion section of an FIRAC directly answers the question presented in the issue section of the FIRAC. This section restates the issue and provides the final answer.

Checklist

- Ensure all issues are rebutted and dealt with clearly and precisely;

- Were all issues corroborated with evidence;

- Is the analysis as thorough as possible?

Variations:

MIRAT – (Material Facts, Issues, Rules, Application, Tentative Conclusion)

IDAR – (Issues, Doctrine, Application, Result)

CREAC – (Conclusion, Rules, Explanation, Analysis, Counterarguments, Conclusion)

TREACC – (Topic, Rule, Explanation, Analysis, Counterarguments, Conclusion)

CRuPAC – (Conclusion, Rule, Proof, Analysis, Conclusion)

ILAC – (Issue, Law, Application, Conclusion)

……………………………………………………………………………………….

This article was written with help of Lear Law Better Video Lecturing, Yale Law School Legal Scholarship Repository and Richard LeGates’s Article.